A photo forward post today.

It’s cold in Los Angeles. It might be colder where you live, in fact, it probably is - but the buildings here are old and thin and I wake up with my bones already chilled. I bring my space heater from room to room and point it directly at my feet, my ankles, sometime I place it on a chair next to me, to warm my hands. Olivia bought the space heater for our old office, and before we vacated and abandoned the premises that first week of Covid, never to return, she told me to take it. Somehow she knew I would need it.

This time of year I always think of my high school swim coach, reminding us that the longest uninterrupted stretch of the school year is from the first day until Thanksgiving.

I still visualize the year in these terms: the school year. I wonder if this will ever change.

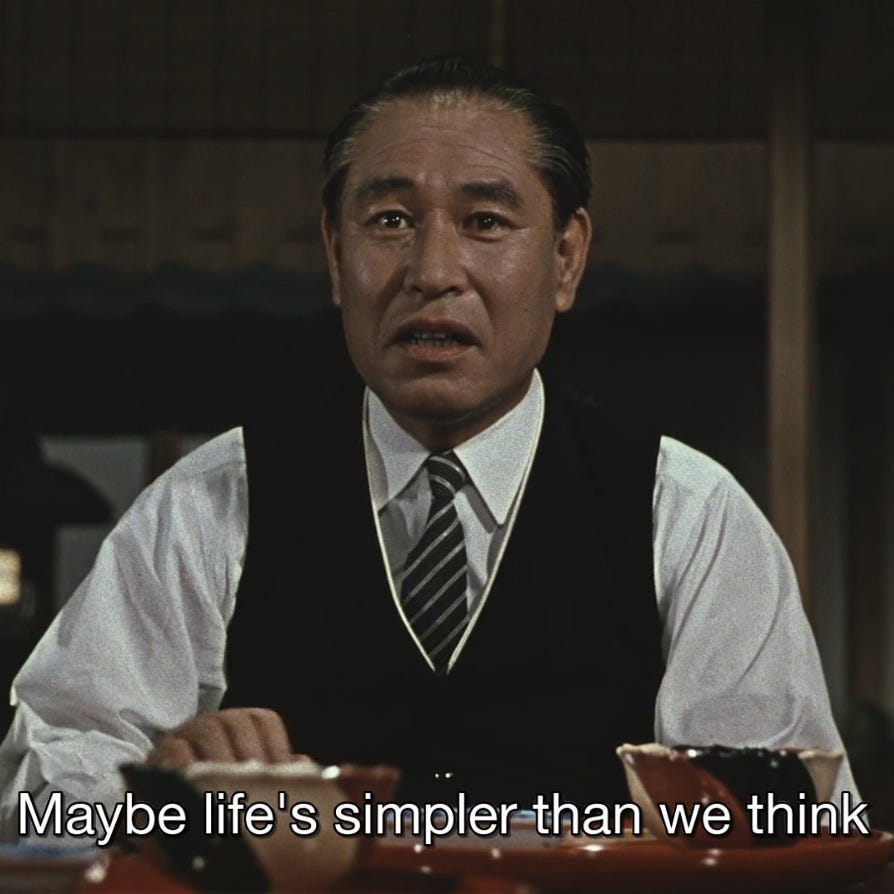

Yasujiro Ozu, the master midcentury Japanese filmmaker. Late Autumn (which you can watch for free here), as well as Late Spring, Tokyo Story, and Early Summer, are examples of shomin-geki: films that revolve around the quotidian lives of post-war middle class Japanese families.

Imagine 1960, Japan. Just 15 years after those two detonations. Destruction and death, the force of which the world had never known.

Ozu used the same lens throughout all of his films; every single shot taken on a 50mm. It’s said that that focal length most closely resembles how the human eye sees, but cinematographers quibble with the exact specifics of that claim.

“One cannot isolate the information given by the eyes from the processing performed by the brain. When looking around you, the brain concatenates images from different focus distances and directions, a bit like the panorama mode of some cameras. And it uses the long term memory for object recognition.”

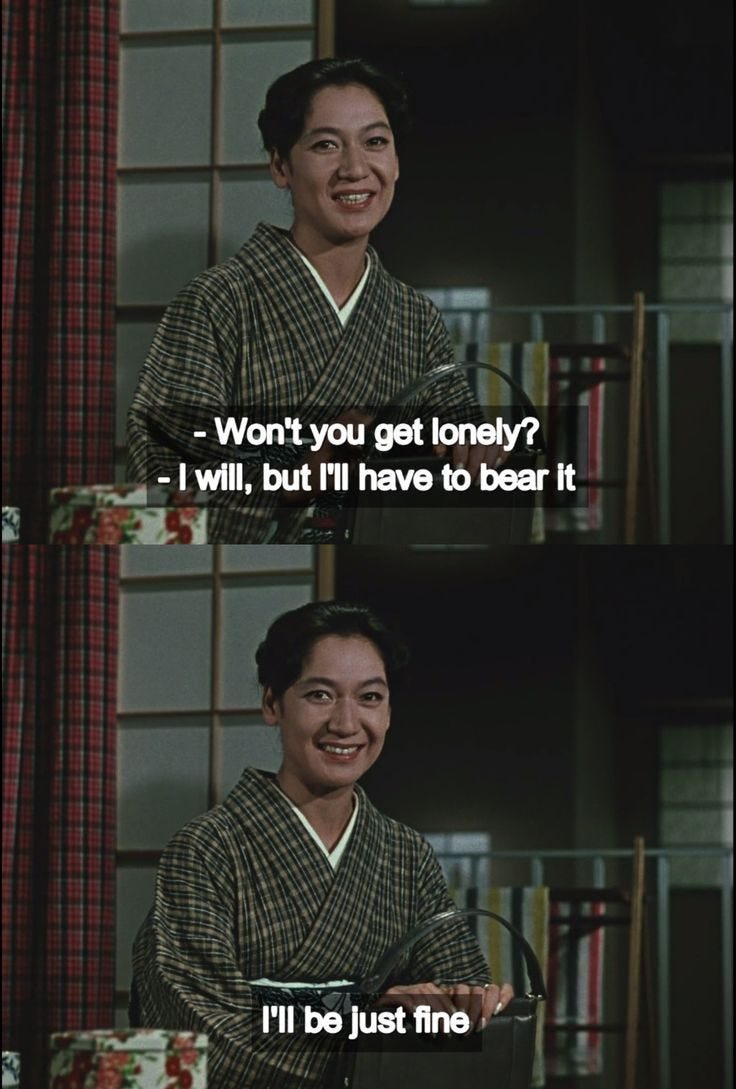

In Late Autumn, a widowed mother (Akiko) encourages her daughter to find a partner for marriage. She is helped by three friends of her late husband, all who offer suitable prospects for Ayako (the daughter). But Ayako is reluctant. She doesn’t want to get married and move out, because then her mother will be all alone.

It can be an odd experience, watching an Ozu film: they’re very placid and restrained, and yet incredibly moving. Late Autumn is characteristically mannered and static - the camera barely moves, save for a few assured tracking shots.

One can’t help but feel like something horrible must be bubbling underneath it all, that something is about to crack wide open and swallow us up into an inescapable darkness.

But then it doesn’t. Then it isn’t that at all.

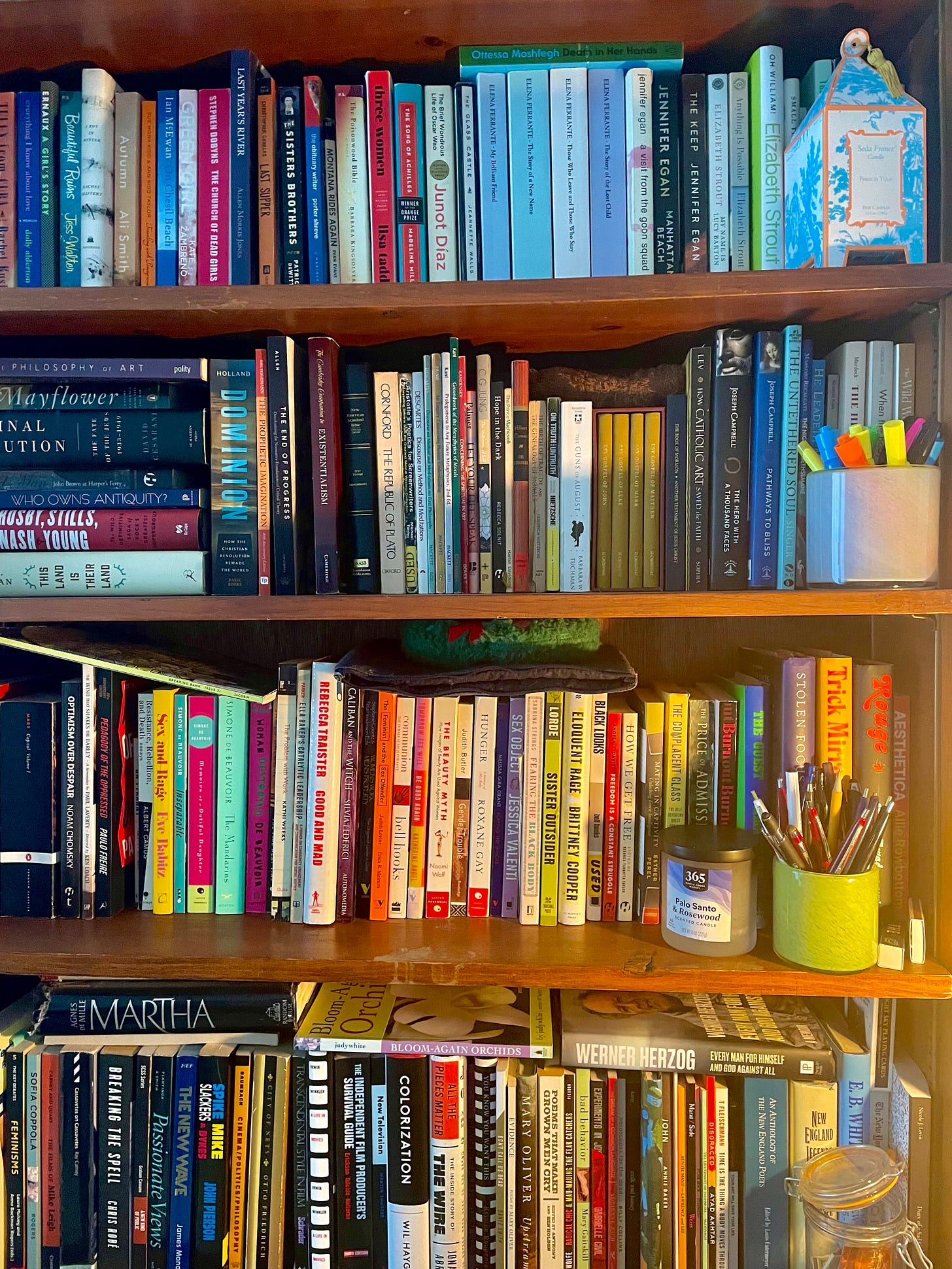

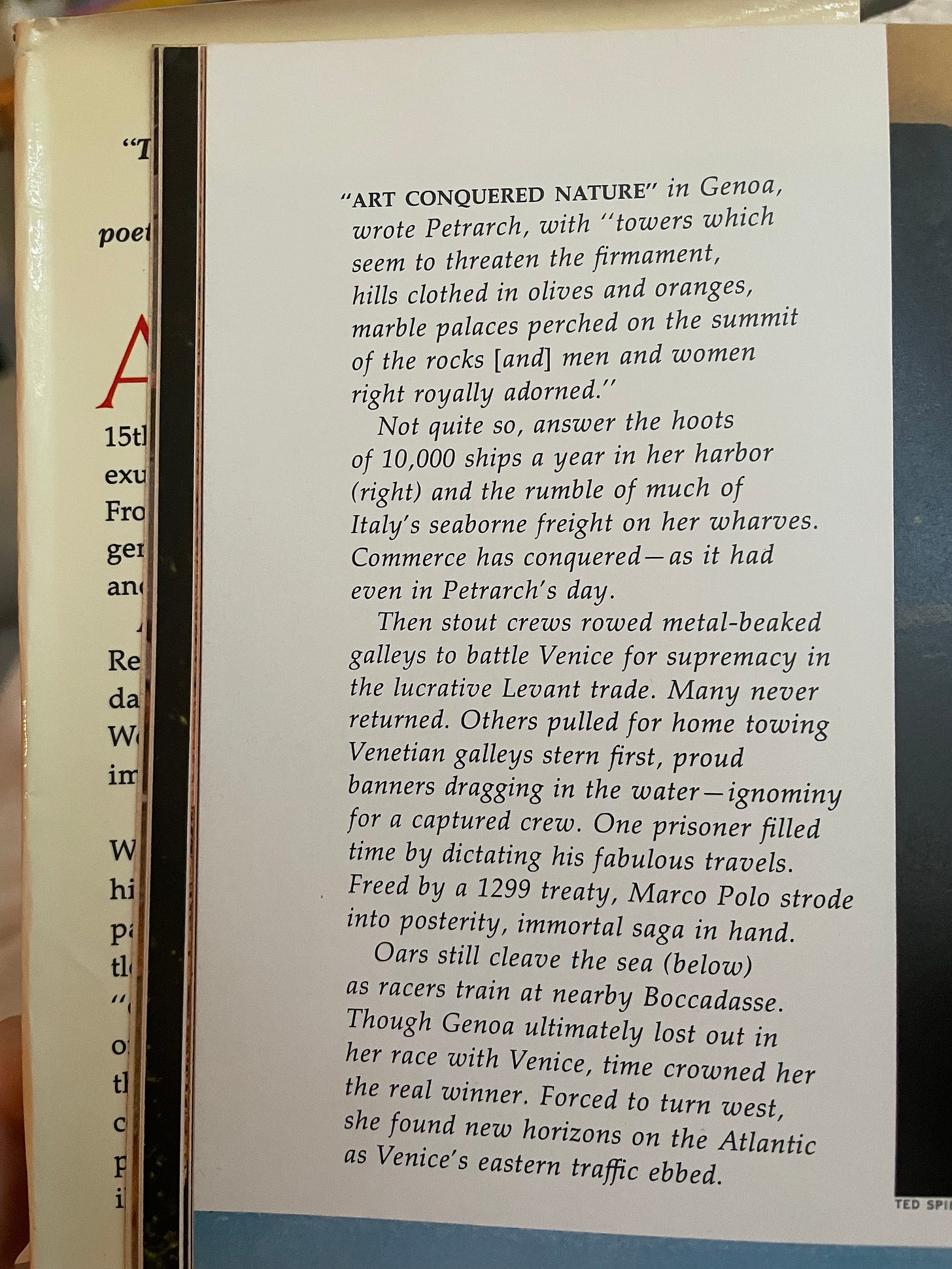

Evan bought this beautiful National Geographic coffee-table book for a dollar at a bookstore in Carpinteria, and I finally cracked it open this past weekend. It’s filled with gorgeous images and essays chronicling the progression of the Renaissance: it’s a textbook and picture book at the same time. Apparently there’s a whole collection of these types of NatGeo books, which I now want to collect.

“By stressing the dignity of man and his creativity, the Renaissance bequeathed an imperishable legacy. Men may stray from its ideals, but eventually the magnetism of the age pulls them back into an orbit of symmetry, proportion, and order. Fortunately for mankind, we cannot escape the influence of the Renaissance, which taught us to utilize the best of our classical heritage, to develop all sides of our personalities and powers, and to appreciate beauty in myriad forms.”

Louis B. Wright

Hirayama: Did you feel the earthquake last night?

Mamiya: Was there one? I didn't feel it.

Hirayama: Yes, there was. But just a small one.