It’s mid-November. It basically starts getting dark at noon. We’re all exhausted. You should watch Mildred Pierce.

I don’t know why this film is a comfort favorite of mine - it starts with a murder and chronicles the devolution of the most menacing mother-daughter relationship of all time - but for some reason I find it to be the perfect cozy but not-quite-winter-yet-watch. Yes, it takes place in Los Angeles, but this isn’t the sunny, beachy, floral LA: this is cold and rainy LA. This is shadowy and dark LA. This is Glendale, as Veda Pierce reminds us repeatedly. Not Pasadena. My love of this film and associations with comfort seems similar to how True Crime fans love their grisly and gory podcasts: a paradoxical blanket of comfort, the murder and crime real only in the ear canals.

The geography of Mildred Pierce has always intrigued me. After she opens up her restaurant, Mildred’s friend Ida muses with a twinge of snark that "I’m sure you’ll do very well, especially with Glendale right next door.” She’s referring to the restaurant being in Pasadena, Glendale’s much richer next-door neighbor. This tension between Glendale and Pasadena is a prominent through line through the film, one I always found fascinating as an outsider who, before living here, could barely tell you the difference between Los Angeles and Hollywood.

There are quite a few lines in the film that only someone entrenched in the architecture of the place would be able to write. Based on the novel by James Cain, the script was written by Ranald MacDougal, a man whose biography is emblematic of a vastly different time in Hollywood, when it was possible to be born into an impoverished family and raised by a union organizer and strike-agitator father, whose frequent bouts of unemployment led to his son drop out of school before 8th grade. Ranald got a job at Radio City Music Hall before crossing the street to Rockefeller Center where he submitted scripts under a pseudonym and was soon hired by NBC despite being under 18.

Glendale is quite far from the beaches that make LA famous. But there are numerous seaside scenes in the film, as Mildred’s lover Monte Beragon has a beautiful home out west. From Glendale it takes (generously) an hour to get to the beach, but it might as well be a universe away. Water plays a huge supporting role, as it does in many Noir films: an early scene in Mildred Pierce finds our protagonist on the Santa Monica pier, about to jump to her death, before being interrupted by a police officer. The moments of primal intensity tend to occur by the water: murder, suicide, sex. The rest of the plot, vacillating between Glendale and Pasadena, is concerned with society, with the intellect - the prefrontal cortex to the water’s amygdala. Mildred is landlocked: trapped by the pressures of neighboring Pasadena, pressure intensified (and perhaps manufactured) by Little Miss Veda Pierce, the most vicious young woman in the cinematic canon. But to give her just a bit of credit, Veda has grown up amongst a staggering, in-her-face display of wealth disparity, and while her younger sister Kay hasn’t been nearly as affected by it, I am often refreshed at Veda’s unabashed, unabated dismay at the lot she’s been dealt. As I’ll get into later in this piece, sometimes I find outward admissions of jealousy quite honorable.

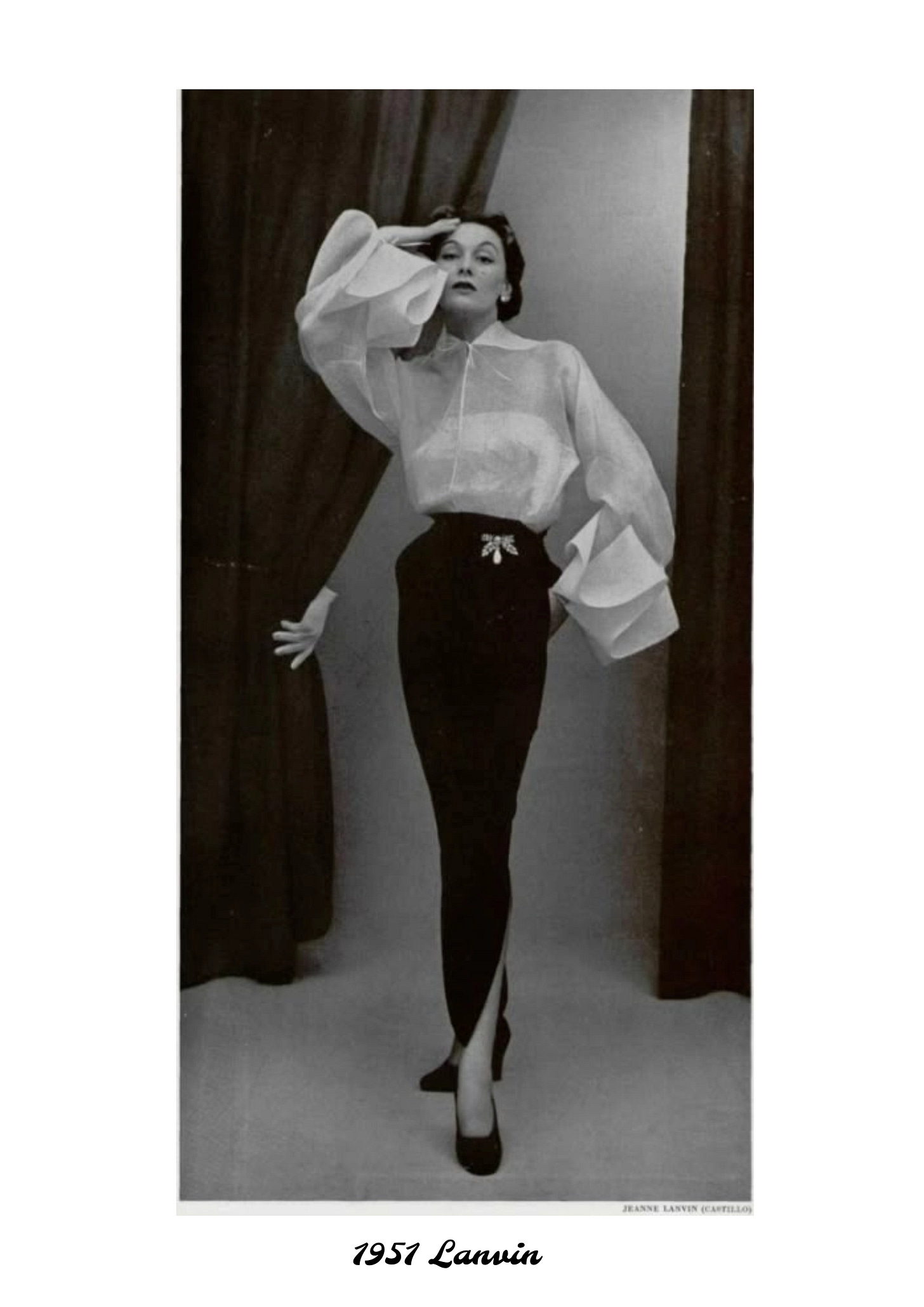

Joan Crawford has a face built for the camera.

In many ways I do really mean built: there were rumors that she had her back molars removed from her jaw, allowing those perfect, angular cheekbones to perfectly frame her wide mask. I’m always fascinated by such tiny insights into “beauty treatments” of the last century, when stepping under the surgeon’s knife was so much rarer and riskier. Now, I can’t even get my skin checked for melanoma without being offered Botox at a tantalizing discount. It strikes me that there must be a correlation between plastic surgery/ botox/ fillers and a decline in good lighting in Hollywood: someone like Crawford would’ve murdered any gaffer who dared allow a crinkle or wrinkle to appear on celluloid. Even the baggiest undereye was no match for a little vaseline on the lens and a direct hard key + soft fill lighting combo. I once read that in their closeups, cameramen often used to shoot actresses just slightly out of focus to further de-emphasize their natural contours, a technique that strikes me as just a little poetic.

Today, the cameras are all HD, 1millionK resolution, and not a blemish (or an overfilled lip) goes unnoticed.

I leave it to you to decide which you prefer.

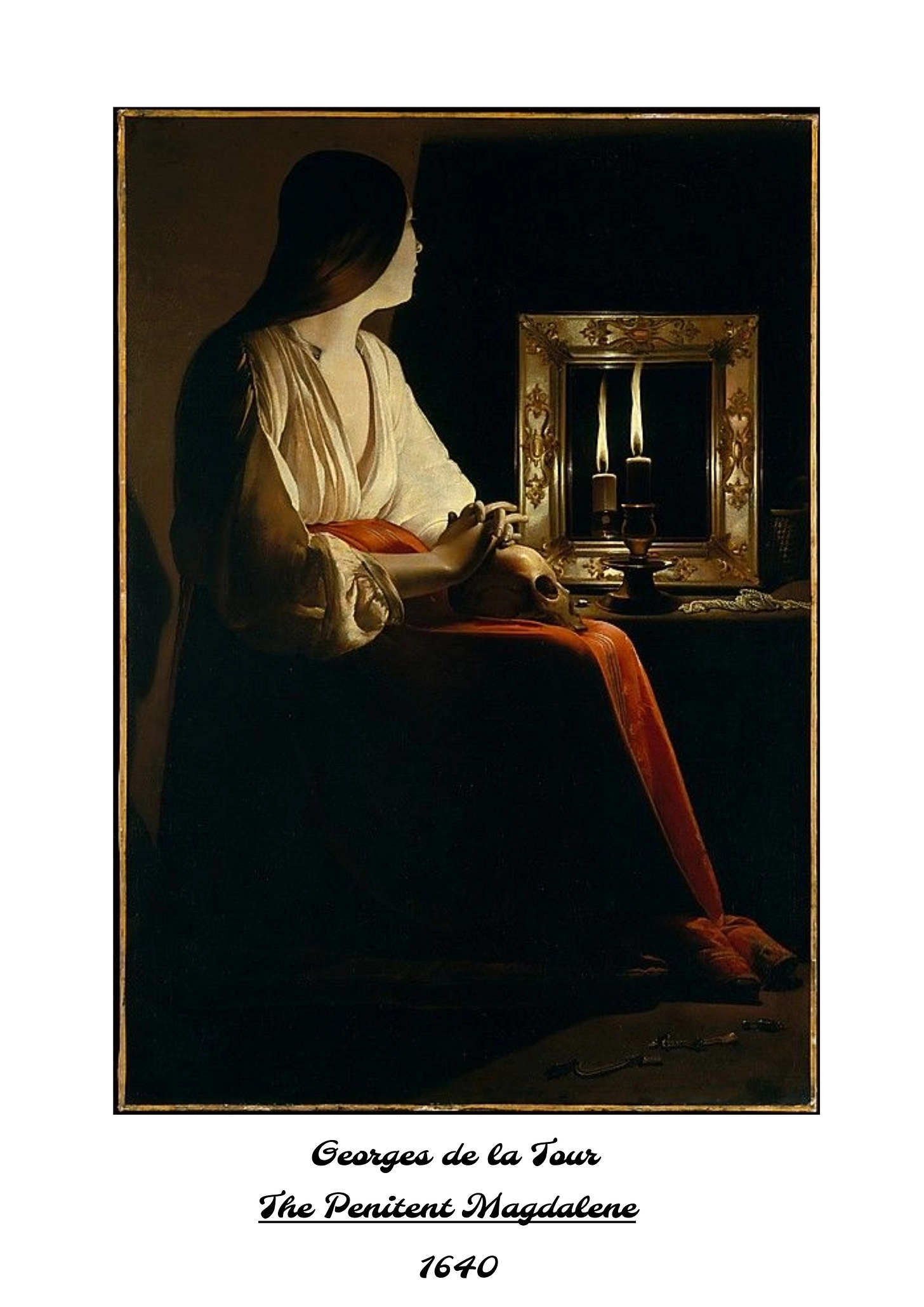

The light on Mildred tends to cut off through her face, softly in the first half of the film, then astonishingly sharp as the story unfolds. At least one eye always remains clear, except when it comes to Veda. Veda is Mildred’s daughter, and is, in a word, wicked. But the question is, was she born this way? Or did her mother have something to do with it? Mildred deludes herself into believing that if she makes enough money, buys enough status in society, if she does enough, Veda will love her. How much is Mildred to blame for enabling Veda? Or, to use a title of another midcentury thriller, is Veda just purely a Bad Seed?

This manipulative relationship climaxes with Mildred’s “I’ll get you anything, everything you want, I promise” scene, and this watch I was struck by the similarities between this scene and Scarlet O’Hara’s “I’ll never go hungry again,” moment in Gone With the Wind. But while Scarlett soon rises from this physical and emotional abyss into triumph, Mildred, herself playing a part in her manipulative cycle of trauma, still has so much farther to fall.

Joan Crawford was one of the many young actresses who would’ve killed to play Scarlett O’Hara, but finally landed her first Best Actress Oscar with Mildred Pierce. Apparently, Crawford wanted the role so badly, correctly foreseeing it as her own vehicle for onscreen infamy, that she left her home studio of MGM after 18 years for Warner Brothers where she knew better roles awaited her. Crawford’s eye for juicy material outweighed the apprehension other contemporary actresses felt toward the role of Mildred: they believed playing a matronly character would age them, and didn’t want to believably play a woman with a 16 year old daughter. But Crawford’s gamble paid off, and she won the top prize for it. Famously, however, she didn’t attend the Oscars ceremony: she believed that Ingrid Bergman would win for The Bell’s of St. Mary, and didn't want to be shown on camera losing. My, how celebrities’ relationship to the public has shifted!

In some ways, I really miss this relationship: tabloid-shy celebrities, narrative savvy gossip columnists, an overarching sense of shame in our public consciousness. I’m about the last to remark on this, but the lack of separation between star and audience has ruined so much of what must have been so delicious and exciting about celebrity in the past. Once we can see celebrities so up close and (oftentimes way too) personal, their sparkly sheen tends to reveal that it’s masking a whole lot of desperation. I’ve observed that it’s particularly noticeable in Gen-X celebrities who begrudgingly moved over to social media and now (for all outward appearances) embrace it: where stars were once reticent to talk into their front facing camera, it’s hard not to go a week without seeing a childhood favorite of mine make a fool of themselves for a few clicks. I noticed this recently with Kristin Davis, my absolute ICON in all things style and sensibility: she posted some video of her young daughter making fun of her for not knowing what “rizz” means or something, and although it was cute and charming and all in good fun, there was something about it that made me sad. A hint of desperation, perhaps, a tiny voice wondering if she would be putting herself out publicly in this way, in her pajamas, at her massive kitchen island, for all to see if she didn’t have followers to gain, content to engage with, brand deals to keep up.

I’m not saying we shouldn’t know ANYTHING about actors and actresses' personal lives. Quite the contrary. It’s just that we forget that before social media, the dissemination of celebrity life was an art (or at least a delicate craft) perpetuated by some truly shrewd minds. Tabloids once were the mediator of information about actors and actresses, and legendary gossipists like Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons were experts at knowing how to manipulate information so that it ultimately served the big business of movies (or really, the Studios). There’s a great podcast series on these two women of the press from You Must Remember This - I highly recommend it to understand just how calculated all of this stuff once used to be, and how smart Parsons and Hopper truly were.

Now actors must be their own publicist, photographer, and gossip-planter… and let’s just say, they’re not doing a great job.

So Joan accepts her Oscar from bed, totally not because she fucking hates Ingrid Bergman but because she’s sick, seriously! Offscreen stories like this were once encapsulated into Hollywood’s overall lore, and here’s the thing: I really believe that all of these little meta-narratives then metastasized and evolved, ultimately having a hand in delivering some truly explosive onscreen performances. Without rivalries between actresses, we would have no Joan vs. Bette, or Vivien Leigh vs. everyone. But yes, I can hear the concern arising: Isn’t it better we aren’t pinning women against each other in competition like this anymore? Shouldn’t we hold the press to a higher standard so that our daughters don’t grow up and repeat this callous behavior? So that we all hate women just a little bit less?

It’s a valid concern, but I’d answer with another one: Are we less jealous of women onscreen today because we’ve lobbied the media to stop pitting us against one another? Do we hate women less?

Are you less jealous?

To me, it seems that this “high road” approach to the entertainment media’s language towards women, plus the encroachment of social media into all aspects of our daily lives, has only succeeded in forcing us to internalize our jealousy. I’m not ready to say it is Definitively A Good Thing to criticize and pit celebrities against one another, I just know that women like Joan Crawford could absolutely handle the heat, and it was in fact part of the overall lore that made her so famous. [and wasn’t it fucking awesome when selena gomez was seen talking shit about kylie jenner and timothee chalamet at the golden globes?! hardworking americans deserve more gossip like this!!!]

The reality is that there’s never been a time when actors were more accessible, but less interesting.

When the Giants of Golden Hollywood, with their competing meta - narratives met onscreen… let me just say that performances were better for it! Whatever Happened to Baby Jane is a bizarre movie that only lives on in cult-like perpetuity because Joan and Bette knew what their audiences wanted - no, deserved after decades: to see them finally battle it out onscreen. Because that’s what’s at the core of this, for me: my belief that we need to get back to an understanding that the behavior of actors and actresses does not reflect on society as a whole, and they should not be held up paragons of moral virtue. At some point in the past decade we forgot this. From a reality star as our once and future president, to the millions of dollars spent on celebrity political endorsements, I think most of us are about ready to throw in the towel on celebrity virtue culture.

In the 20th century, Hollywood rivalries were able to be contained in Hollywood because Hollywood was, well…. Hollywood. The rest of the world, the rest of the world. A healthy container for unhealthy behaviors, maybe. And if those unhealthy behaviors lead to explosive performances, what more could we want?! It seems as if the ecosystem was working according to some divine plan! Maybe this is a cancelable take, but I’d just like to remind you that I make no money off of this writing so at least you can’t accuse me of profiting off of hatred. I just do it for the love of the game!!

All I’m really trying to say is twofold: one, that the offscreen tabloid world in Old Hollywood surely had something to do with why onscreen performances were better, and two, on the other side of the same coin, we do a disservice to the craft of acting when we know so much about actor’s personal lives because it severely limits us from fully subsuming ourselves in the world of the film. It’s a fine line between knowing just enough about Joan Crawford so that you buy a ticket to her film and can feel her personal life simmering somewhere hazy in the nondiegetic distance vs. trying to believe that [insert your least favorite gen z actor here] is a different person than the one we just saw hawking questionable diuretic pills and $400 eye cream she didn’t even pay for herself on her Instagram. We shouldn’t know nothing about actors - we should know just enough. How much is that? Women like Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons knew very, very well.

But back to Mildred Pierce.

Well… I actually don’t have anything else to say about it.

As you tuck into this incredible film,

kick start your thanksgiving prep by making one of mildred’s famous pies,

And finally, call your mother and apologize for something (you know there’s something).